As Californians awaited the first day of summer, they were also bracing for a significant storm system to roll through the state, fueled partly by monsoonal moisture and partly by a disturbance in the jet stream moving across the region. Although the thunderstorms in the forecast were expected to produce very little rain, meteorologists warned they could still produce dangerous lightning.

While there is no such thing as safe lightning, so-called “dry lightning” (i.e., lightning accompanied by rain that evaporates before it hits the ground) is especially dangerous because it brings heightened wildfire risk. And, in drought-stricken California, that risk is already high enough without lightning.

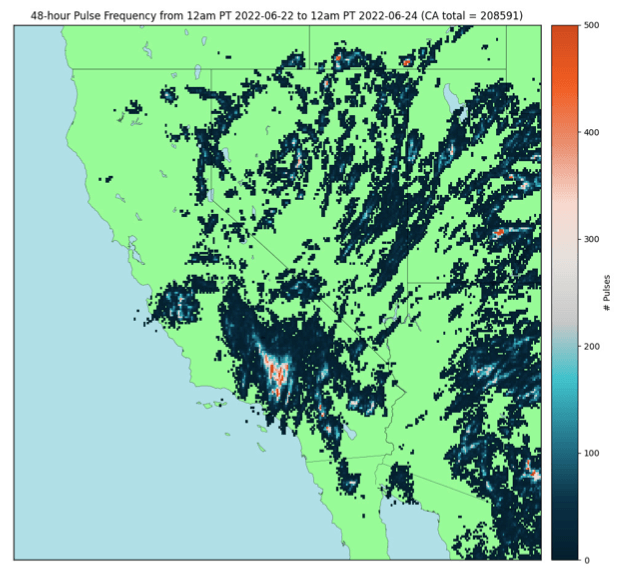

When the storm system finally hit, from June 22 to June 23, it produced more than 208,000 total lightning pulses across the state, including more than 33,000 cloud-to-ground pulses. It was the most lightning the state had seen in a single day in nearly five years.

Wildfire Today reported that the storm did, in fact, ignite a number of small fires. The largest of these was the Thunder Fire, which burned about 2,500 acres before being fully contained. Fortunately, firefighters were able to contain most of the fires without too much difficulty, limiting the total burn area to less than 4,000 acres.

While no amount of destruction is ever good, Californians were fortunate that this incredible amount of lightning did not produce a more incredible amount of fire. For comparison, in August 2020, a similar “dry lightning” storm ignited more than 650 wildfires across northern California, including the August Complex Fire, which became the largest fire in state history. Together, those fires burned an estimated 1.5-2.1 million acres (about the area of Connecticut).

Three factors combined to prevent the outcome of the June 2022 lightning storm from being much worse:

- Rain is thought to have reached the ground along with some of the strikes, especially at higher elevations.

- The active North American Monsoon winds brought high relative humidity to the region, making fuels less receptive to ignition.

- June is still early in the fire season, before fuel moisture drops to critically low levels.